WP5 focus: Proof positive for negative emissions from waste-to-energy

For many of us, tackling waste goes no further than sorting the recycling and putting the bins out. Waste is a consequence of society and, while some progress is being made to reduce the sheer volume generated, Europe has billions of tonnes of the stuff to deal with every year.

The age-old and unsustainable practice of burying waste, known as landfill, is being phased out in many countries. In Scotland, for example, by 2025 it will be illegal to send biodegradable waste to landfill sites.

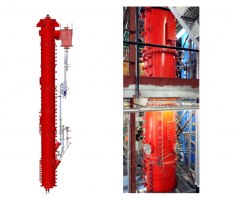

With more waste set to be channelled to waste-to-energy plants, where it is incinerated to provide heat and power, we have an opportunity to reduce the amount of carbon dioxide (CO2) already in our atmosphere if these plants deploy carbon capture technology.

Preparing the ground

The NEWEST-CCUS project is exploring technologies and processes that will help Europe’s waste-to-energy sector exploit this potential. One team, in particular, has a special focus on bringing all these strands of research together.

Scientists at the University of Edinburgh are working with colleagues from SINTEF in Norway, the University of Stuttgart in Germany and TNO in the Netherlands on Work Package 5. As well as comparing the different carbon capture technologies that could be deployed by waste-to-energy plants, the team will also evaluate the market for their uptake.

Dr Camilla Thomson of the University of Edinburgh, who is leading Work Package 5, explains: “We’ll estimate the size of the potential market for carbon capture, utilisation and storage (CCUS) technologies, taking into account current and anticipated trends in waste types and waste quantities. We’ll also consider the plants themselves and any potential constraints of individual carbon capture technologies. We hope the results of these analyses will prove invaluable for the waste-to-energy sector.”

Dr Thomson’s team will also assess environmental impact and conduct a full life-cycle analysis; in other words, will CCUS with waste-to-energy deliver net zero carbon or, even better, negative CO2 emissions?

Carbon negative

The term “negative emissions” effectively means taking more CO2 out of the atmosphere than you put in. A sizeable proportion of Europe’s annual waste contains organic material – food, plant or animal waste – which by its very nature contains carbon that, unlike the carbon in fossil fuels, originated in the atmosphere. This would normally be released back to the air as CO2 when this biogenic waste is incinerated.

However, if the waste-to-energy plant includes carbon capture technology, the trapped biogenic CO2 can either be transported and permanently stored deep below ground in geological storage sites or used to make new products, such as synthetic fuels or building materials.

Some estimates suggest that the waste-to-energy sector in Europe could deliver as much as 2.8 billion tonnes of negative CO2 emissions by 2100 if the anticipated 4 billion tonnes of municipal solid waste is burned in plants deploying carbon capture.

Dr Thomson says: “With waste-to-energy operations, this waste is already being transported to treatment centres and in many countries in Europe it is already being incinerated. In NEWEST, as well as enhancing carbon capture for the waste-to-energy sector and assessing the potential market for the technology – either retrofitted or as part of newbuild plants – we’re estimating the potential for negative emissions across Europe if CCUS is deployed effectively.

“We’re gathering data and characterising the types and proportions of waste arriving at plants to provide a life cycle assessment for waste-to-energy with CCS for the whole of Europe. It’s a labour of love because waste profiles vary, not just from country to country, but from city to city.”

It sounds almost as daunting as cleaning the Augean Stables but the team is up to the challenge. And with Europe still forming its plans for meeting Nationally Determined Contributions as part of the United Nations’ Paris Agreement – and keeping in mind the pivotal COP26 talks in Glasgow later this year – waste-to-energy with CCUS could present a big win.

Dr Thomson adds: “Our work on waste characterisation is just part of the overall picture. We’ll also analyse the flow of carbon – both biogenic and anthropogenic – and other pollutants through the system and assess the life cycle impacts of the waste-to-energy with CCS plants. Carbon capture and utilisation processes will also be under scrutiny.

“Studies involve drawing on detailed information provided by our academic and industrial project partners, which I think is what really adds the extra value to this project – we’re bringing data from all parts of NEWEST together to do this assessment. We’re confident that we can provide an estimate to illustrate just how important CCUS on waste-to-energy can be for delivering negative emissions across Europe.”

Zero ambition

The NEWEST project wraps up in 2022 with findings expected to be welcomed by the waste-to-energy sector as it rolls out plans for realising its net zero carbon ambitions.

Dr Mathieu Lucquiaud, of the University of Edinburgh and NEWEST-CCUS Principal Investigator, says: “Our research will help to quantify the contribution of the waste sector to negative emissions at the city, regional and national level across Europe. In a net-zero society, waste could become a strategic resource of negative emissions, without competing for land availability with biomass production.

“What we need now is for regional and national governments to ‘buy in’ to the value of negative emissions from waste when planning new waste-to-energy facilities. It’s also crucial that life cycle analysis methods account for negative emissions from waste. It is currently common practice to discount biogenic carbon emissions. We hope that our work can demonstrate how this can be done.”

Words: Indira Mann, SCCS